In this series, I will present parts of my dissertation, ‘What strategies, activities and methods would help develop the teaching of music improvisation in UK secondary school education?’. I aim to give you insight into my improvisation research by informally presenting my findings, opinions and thoughts. It may start a discussion of the justifications, merits, and advocations for music improvisation or completely put you off and double down on why improvisation should be left out of music education. Either way, I believe it’s a meaningful conversation.

Results from Interviews & Conclusion

Background

The interviews highlighted the individual pursuit of learning improvisation and an inquisitive mind to find answers to questions their secondary education did not ask. Their experiences highlighted a divide in music education, whereby improvisation did not feature in their school education, or worse, was treated with a callous dismissal in ID B’s discovery of improvisation. For other examples, teachers were well-meaning but ill-informed to give proper assistance in developing improvisation skills. For ID C, improvisation was barely featured in his secondary education due to the pre-eminence of Western classical learning. The survey showed that only a few teachers come from an improvisational background in training as musicians and teachers. However, most teachers use improvisation in their curriculum (just under half for co/extracurricular). By anonymising the identities and backgrounds, the data did not represent a true reflection of their experiences. In hindsight, it should have been captured as an open-ended question like the one asked of the interviewees. This was a missed opportunity to look at the phenomenology between the survey and interviews to see how the experiences compare, such as the divide between secondary education’s relationship with improvising. Where is the duality between curricula and self-learning improvisation? And what is the role of an explorative mindset in learning improvisation?

Definition

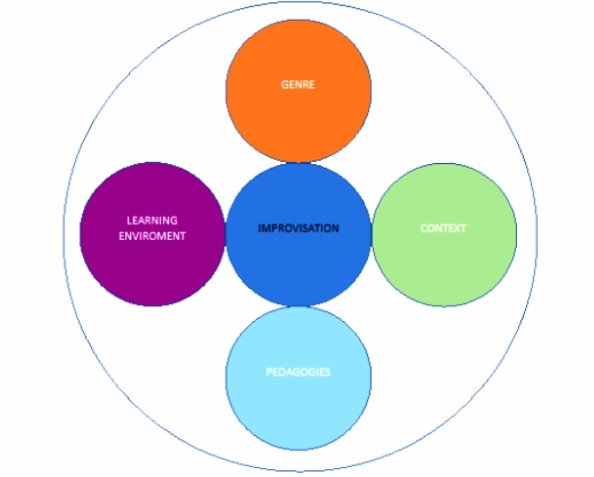

Regardless of improvisational background, references to spontaneity and expressive and momentary music making were identified as characteristics of improvisation. These characteristics will be essential to secondary teachers in creating rationales for strategies, activities, and methods and advocating improvisation in one’s practice. Improvisation as a musical language (musicianship, notation and music theory) could eliminate barriers to demystifying improvisation by describing it as a language linked with human experience. Mentioning composition was an interesting definition that can also help bridge a better understanding of improvisation in secondary. Teachers have a better chance of promoting strategies, activities, and methods for devising, embellishing, and experimenting with musical ideas while not taking students out of their comfort zones to create improvisation (ID D).

Genre

Genre-led teaching of improvisation featured heavily in the interviews and survey questionnaire. This may have been due to an association that genres such as jazz strongly linked to improvisation (Larsson & Georgii-Hemming 2018). A potential issue with this association is secondary teachers presuming that to teach improvisation, one must know jazz music. When designing the project, there was no emphasis placed on genre, as the intention was for participants to reveal their opinions on genre’s role when teaching improvisation. Not mentioning genre in the survey questionnaire and interview invitations should have clarified any ‘assumptions, world view and theoretical orientation at the outset of the study’ (Merriam 1988, 169). As a result, jazz and blues emerged as preferred genres, which could cause issues for teachers unfamiliar with the genres wishing to teach improvisation. Further studies on other genres, such as Early music and Indian classical, will be beneficial in ascertaining if these genres would be suitable for improvisation in secondary school.

Strategies, Activities and Methods

The interviews shared different perspectives on what would be effective when teaching secondary improvisation. ID A’s emphasis on the neurological approach, ‘right brain’ activities and methods based on rhythm, pulse, groove and repetition is reminiscent of Sarath’s advocation for his Transstylistic method, as both mentioned repetitive framework for rhythm underpinned by a melodic and harmonic pitch framework (Sarath 2009), backed up the survey. ID B’s focused on the ‘pitch framework’ too, with the use of rhythm implied in his examples but not the main focus. ID C’s concentrated on learning by listening, genre attributes and composition by devising tied in with musical elements based on strategy and method. They also offered good exemplars for secondary teachers to use, playing the first chorus of a solo only. This advice is useful, teachers will need to take care in the exemplars they select to not put off students by making them feel improvisaiton is unobtainable.

All four represent strata for improvisation pedagogy, with the survey questionnaire sampling strategies, activities and methods mainly in line with Simon’s approach to curricular teaching. Cocurricular’s data was surprising in that it offered fewer suggestions. The presumption was that teachers would use strategies, activities, and methods in cocurricular activities because there would be more opportunities for improvisation and fewer limitations to contend with in curriculum teaching.

Away from a more prescribed approach, the survey’s sugestion of improvisation for special needs schools deserves some consideration. Using sounding boards and allowing their students to improvise with an open scaffolding could be a great way to introduce improvisation to a group already confident with instrumental skills and have the freedom to play without restrictions. The concern is that it takes secondary improvisation back to the original issue of lacking formal strategies, activities, and methods. However, special needs and music therapists’ teachings could provide ‘a psychological template.’ (ID A) for teachers to use.

The use of improvisation at SEN schools is also worth noting due to its flexibility and explorative nature. Using assessable musical instruments for students to improvise with an open scaffolded approach could be a great way to introduce improvisation to a group already content with instrumental playing and freedom to play without restrictions. There is potential to expand improvisation pedagogy and research in the SEN area (SEN and music therapists’ teachings could provide a psychological template for teachers to use) and, most certainly, at the primary education level.

A Model for Secondary School Music Improvisation (Conclusion)

Define what improvisation Means to You

Most people may think of improvisation as an ‘on the spot’ act, but that is just the tip of the iceberg. Good improvisers plan and practice enough ‘musical vocabulary’ to perform from memory, in the moment, in any context and many ways. Improvisation takes on different forms, whether a solo within an ensemble performance, generating ideas for a composition or embellishing a song structure or chord progression. However you define improvisation, this is what it will mean to your students.

Genre/Topic

Genre is essential to learning improvisation as it contextualises the learning and provides students with a framework for the vocabulary they will develop. The first thing to consider is what genres/topics you are comfortable modelling and teaching. There is no point teaching an unfamiliar genre/topic, as you will not know if the improvisations are stylistically correct. When you choose your genre/topic, introduce stylistic characteristics and typical phrases as you go, with fewer stylistic pointers at the start. You can scaffold more genre-specific traits as students develop their skills and confidence. Composition is an accessible topic. Get students to devise ideas in rehearsal time and perform their creative ideas later. This method does not use ‘real-time’ improvisation but uses improvisation at the heart of the learning. Blues and Jazz are the most straightforward genres, as many recorded examples of great improvisations exist. Some of your students may already know that Jazz uses improvisation.

Curricular/Co & Extracurricular

It is noteworthy to consider whether you want to teach improvisation for curricular, co/extracurricular teaching or both. Your choice depends on your cohort, class size, available breakout space, equipment, department’s schemes of work and plan and ethos for the learning. Your vision for improvisation will be necessary for how it fits in with the teaching; curricular improvisation allows it to be accessible for students regardless of instrumental skill and explores musicianship skills to develop their improvisation vocabulary. Co/Extracurricular teaching will enable you to work directly with the musicians/singers in your department to establish improvisation skills in ensemble and performance contexts. Both pathways will help your students with confidence in performing and social skills and provide a place where ‘mistakes’ are very much part of the learning process and essential to learning.

Strategies, Activities & Methods

Scaffolding is key, as well as using practical starters, main tasks and plenaries to get students listening and engaged musically with improvisation. Starters should focus on using body percussion/movement and voice to focus on repetitive call and response (teacher-led then moving to student-led) tasks designed to engage the ear and quickly get students improvising. Patience is key; students will be scared/reticent at first but will warm up once they feel safe doing the task. How you plan your student’s learning is important too. Do your students learn improvisation individually? Or in groups? Do they practice their improvisations to a backing track? Whatever you plan for the learning outcomes will determine what they show you as improvisers.

If you plan for performance-based improvisation, the best place to start is with instruments. Keyboard/pianos are the obvious choices, but xylophones are just as effective in connecting the instrument with creativity. If you use keyboards/pianos, the back keys (pentatonic notes) are easy to teach call and response patterns and get students to make their improvisations. Keyboard/Piano’s are great at improvising chord progressions/shapes. White keys (C major/A minor) present a more significant challenge, so narrow the keyboard area to an octave for less confident students and encourage a broader range for more confident ones. Stick with triads/dyads (root and 3rds) for the less confident student and inversions/extended chords for the more assured. Black/white keys can also be great for composing a piece in binary form as students learn to improvise using both sets.

Whether your students are performing or composing using improvisation, creating a template/guide for them to follow is a must. Developing improvisers requires a bank of ideas to form their musical vocabulary, so careful planning, encouragement of repetition and decision-making are essential. A good way to capture improvised ideas could be to write /record ideas, like a diary. This can satisfy learning progression, demonstrate that students have used aural skills, and show understanding of the learning outcomes too.

Developing a student’s understanding of rhythmic patterns and grooves is necessary to improvise fluently. Students need help with rhythmic improvisation more than melodic or harmonic. Students struggle with cognitive overload, not knowing what to do next, and not having a strong rhythmic vocabulary to fall back on. This is where the ideas bank comes in handy, as it will help students learn and recall ideas to be used for melody or chords. Avoid focusing on numbers and words when demonstrating improvisations and focus on shapes and metaphors. The less information students can process to access improvisational activities, the better. Ideas can be borrowed from what students already learned, i.e. using straight quavers to play a jazz pattern, with compound (swung) quavers introduced later once they build upon prior knowledge to add to new knowledge. Having a sound understanding of stylistic grooves will also be a factor in your improvisation teaching, and this can be developed through call and response, along with clear exemplars of improvisations that model what you teach. Just be mindful of these examples; the first chorus of jazz solos is good to play as the soloist usually takes a while to warm up, and you would not want to scare off students by playing a blisteringly fast and technical solo from the start!

Be mindful of the learning outcomes and create an assessment plan that is authentic to the improvisation you teach. Fluidity, articulation, theme and repetition could be areas you wish to assess. Differentiate for different outcomes. Improvisation can take many forms, whether melodic (selecting notes from a scale), using rhythmic patterns, or comping a chord progression. A well-planned and challenging lesson is achievable even if the results do not show initially. Be patient: students develop at different levels, and it takes time for improvisation vocabulary to become embedded.

Supporting Your Student’s Improvisations

It’s a defining characteristic in professional careers and expresses one’s identity as a creative artist. Improvising can be a transformative experience for your students and help unlock the creative potential for new and exciting music-making.

Most of your students might not feel comfortable with improvising, and the very nature of making music without some form of notation or structure is scary for some. It can also be utterly petrifying and put even your most talented students into a situation where they feel like beginners; after all, creating music without notation is scary! Therefore, an environment where ‘mistakes’ are encouraged as part of the learning process and used as part of improvisation is crucial.

Ensure you give them enough opportunities to improvise in front of people beforehand, letting them know beforehand that it’s ok if they choose not to. Improvising can be a transformative experience for your students and help unlock the creative potential for new and exciting music making, it can also be utterly petrifying and put even your most talented students into a situation where they feel like beginners.

Be mindful of the learning outcomes and create an assessment plan authentic to the improvisation you teach. Fluidity, articulation, theme and repetition could be areas you wish to assess. Differentiate for different outcomes; improvisation can take many forms, whether melodic (selecting notes from a scale), use of rhythmic patterns or comping a chord progression. A well-planned and challenging lesson is achievable even if the results do not show initially. Be patient: students develop at different levels, and it takes time for improvisation vocabulary to become embedded.

Finally, encourage your students to take risks and celebrate successes! It’s tremendously brave of any young musician to stand up and perform an improv, so do not dampen their spontaneity to improvise, even if you are working on non-improvised topics. You will know the true extent of your success when students incorporate improvised ideas in your lessons or produce a solo/piece of music with confidence and imagination.

This proved quite challenging when trying to summarise my research into a succinct and accessible model, albeit one that is in its infancy regarding introducing the idea of improvisation in secondary music education. I will say that I have been overwhelmed by the music community’s response to this, and I have been privileged to speak at a Music Teachers Association conference, Jazz in Education, Music & Drama Expo and Curriculum Music conference within the first year of finishing my Masters. I will post a blog (maybe Vlog, but it has been a while since I’ve done one!) later on, but for now, I thank you, dear reader, for supporting the work I do, and I am excited about the potential impact of our collaborations in developing improvisation and putting it back in its rightful place in music education.

Best wishes,

Michael Wright

Larsson, Christina, and Eva Georgii-Hemming. 2019. “Improvisation in General Music Education – a Literature Review.” British Journal of Music Education 36 (1). Cambridge University Press: 49–67, p.59-60.

Merriam, Sharan. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. Jossey-Bass, p.169-170

Sarath, Ed. 2009. Music Theory through Improvisation : A New Approach to Musicianship Training [Electronic Resource]. Routledge, p.43-83