In this edition, I’ll share how teaching music improvisation has helped my neurodiverse students learn how music is constructed and performed in their own ways. I’ll also discuss how my own neurodiversity informs my teaching strategies and improvisation methods.

As a caveat: My advice is not a one-size-fits-all for students. Everyone’s neurodivergence is different, and much of how we learn is down to personal characteristics and opinions/bias towards a subject. That said, I will categorise neurodivergent types into stereotypical traits, but only to provide an overview.

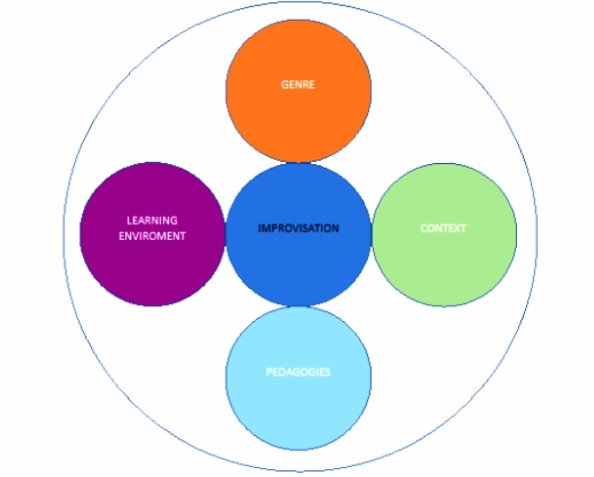

If you have read my previous articles on improv teaching in Music Teacher magazine (do check out my latest instalment on how genre plays a part in music improvisation, see ‘How Informed Is Your Improv?’, you will know that I favour breaking down musical elements into sections to use then as models to improvise with; effective improvisation teaching always gives the student a model/template to use to embellish stimuli in real time. My ongoing development as an improviser and educator leads me to question my practice in both the institutions I work at and the wider community.

I view improvisation’s place in UK music education as mainly autotelic and transgressive, sometimes at odds with the constructs of curriculum and learning. As someone with ADHD and Dyslexia, having to adapt to such constructs has and continues to be a challenge, and I know my students also have similar challenges! There have been many arguments and advocacy on social media about how neurodiversity/SEN has been undervalued in our system both in financial and importance, but rather than focus on what we are not in control of, we can focus on what we can change in our practice and that is how we can help our students. Music teachers are in a unique position compared to other subjects, in that music is malleable enough to be taught in many ways.

In learning contexts, music improvisation can be ‘valued as a way to encourage agency and creativity in students and workshop participants and here, too, issues of freedom and constraint surface’ (Borgo, 2007; Kanellopolous, 2011), though as I have written before, this takes a copious amount of planning and direction to steer the learning whilst not over-directing the lesson (2007, p. 83).

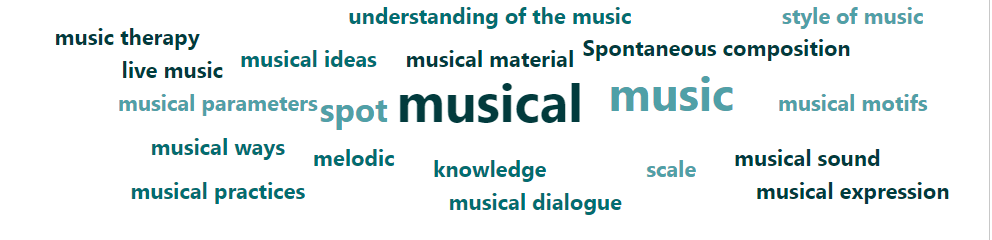

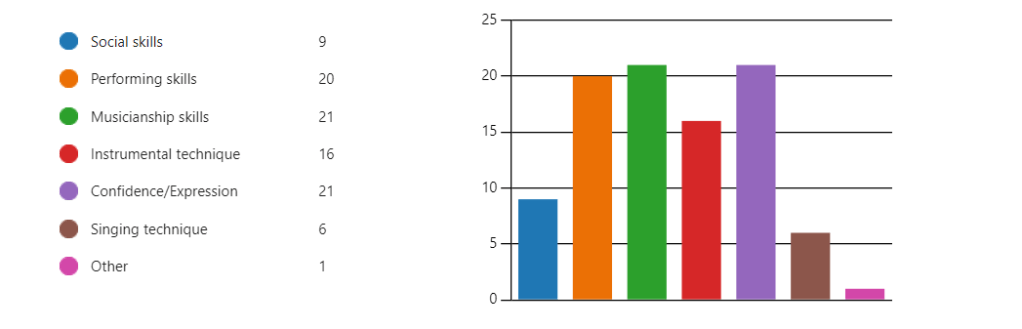

Music improvisation offers a uniquely inclusive pathway for students, as it values process over product, encourages personal expression, allows multiple correct answers, creates a level playing field, and engages cognition, interpersonal skills, and emotional well-being. It does this through timbre, rhythm, pitch, dynamics, and gesture, largely without the reliance on words or text, which can be of enormous benefit to students who are non-verbal or have speech and language difficulties.

Having a lay understanding of what part of the brain controls music and what parts of the brain are affected by neurodiversity, I understand that the right hemisphere is in control of music – pitch, melody, tonal memory and sound. It also controls the creative and doing aspects, which is why I heard the term ‘right brain activities’ (Shmerling, 2017) come up a few times in my research.

The left hemisphere focuses on logic, reasoning and more pertinently, reading, spelling, but also rhythm (Overy et al.,2004). Improvisation is a predominantly ‘right-brain’ activity, and students with dyslexia, for instance, are often drawn to activities such as music, art, acting, and sport; therefore, it might make sense that improvisation suits our inclination for this type of learning. It is also why I have mentioned before in previous articles, and in my research that when teaching music improvisation, avoid activities where students are having to think/process whilst engaging with improvising. It is better to do than reflect afterwards.

I would not advocate a ‘free’ improvisation model in any neurodiverse/SEN setting, curriculum or otherwise. Though there would be advantages to not having any restraints regarding personality, individual expression, or aesthetic differences (Hickey, 2015), not having any boundaries will create problems that I won’t need to go into detail about, such as classroom management, relationship dynamics between students, and, of course, learning outcomes. Teaching music improvisation is no different in its preparation to any other musical discipline.

Teachers, though, must consider their students’ profiles to predict how they will handle music improvisation. How much do students understand the fundamentals of music making? How do students interpret worksheets/resources? How will students negotiate boundaries with one another when the learning has no definitive endpoint? (Hickey, 2015, Borgo, 2007 and Berliner, 1994).

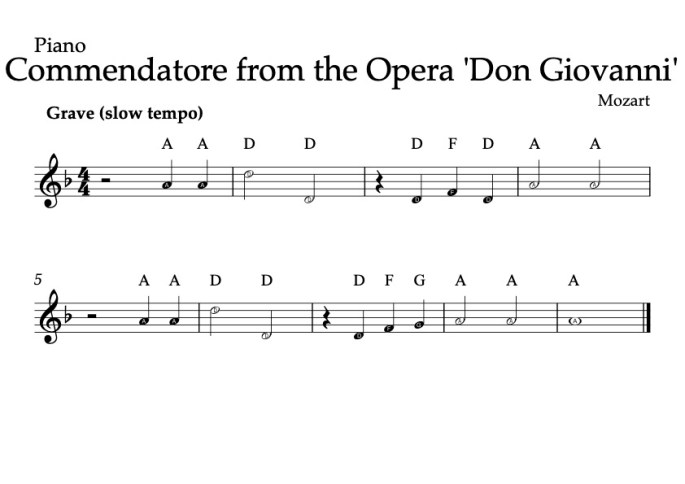

One of the first lessons I learned when teaching students who struggle to access learning, particularly Dyslexic students, is to allow more freedom during an activity. I still struggle to read stave notation to this day, despite knowing everything there is to know about Western staff notation and pitch; dots on a stave confuse me! I know some of my students feel the same, as they tell me. So, I revert to what we have been identified as being good at: aural and sound recognition. Here is a recent example of one of my Y9 students. She struggles with reading and has yet to link letters to pitches and translate them into keyboard input. I taught her the rhythm of a melody (the opening to ‘Commendatore’ from Don Giovanni). Then I asked her to pick three white keys and practice putting any combination of them to the template. As her confidence grew, having a sense of what the passage should sound like, I went on to ask her to play passages from the melody as written, and then improvise the rest:

This is how I first learned to play from notation: listening to the music first, improvising what I heard, learning parts of the chart, then interspersing that with my improvisations until I developed enough confidence to know how the music should sound.

Regarding student focus, it is worth keeping in mind that when students engage with music improvisation, they can either demonstrate a monotropic (i.e. tunnel vision or an ability to focus on a limited number of tasks/interests more associated with students exhibiting ADHD and autistic traits) or polytropic (ability to diversify attention without becoming overwhelmed). A polytropic may handle improvisation better than a monotropic. Still, the latter’s intense focus, if directed well can work better when developing improv skills, owing to their ability to lock in, or at the very least, focus just enough before they get distracted or disinterested. Music improvisation gives students endless combinations of melodic or rhythmic ideas and freedom to experiment without a ‘right’ or wrong’ answer, to keep interest.

Many students with dyslexia and ADHD prefer to memorise their work rather than rely on worksheets. Early lessons emphasise modelling and visual or pitch cues, so by the end, students often no longer need written prompts. I use improvisation and embellishment as extension tasks, building confidence and justifying higher grades. Personally, I also learn best by listening, internalising, and memorising music—I’m sure I could still play the bass part from Jesus Christ Superstar after all that practice! From what I understand about myself, owing to issues with short-term memory, monotrophic cognitive load, and heightened auditory sensitivity; Music must be heard first, before I form a relationship with it. Sound over symbol, if you will.

I must also stress the need for us to be relatable and patient with students. I, like you, have seen when students become dysregulated, lost in the fog of processing and keeping emotions at bay. One does not have to be neurodivergent to understand this. As teachers, we are all altruistic and kind-hearted by nature, but making students feel we can relate goes a long way, and sharing our frustrations and successes with them helps. I have always approached my 1-2-1s with the sense that my student and I are discovering improvisation together; we both hear and experience it at the same time. That is something the notated score cannot do, as the teacher already knows it, so the student is merely trying to prove they can play it. Once your student(s) improvise, provide real-time feedback and mirror their improvisations, pinpointing where they did well, where they can improve, and, more importantly, what they can do next to develop more ideas. This method helps students create their own ideas without giving them the answer. For some SEN students, having multiple paths is liberating, knowing that any one they take will lead to the correct answer; for others, the ambiguity and lack of clarity about what is the ‘right’ answer will frustrate them. To that,

I have this analogy:

‘6×2=12 is correct, But so is 4×3, and 20-8, and 24÷2…’

Improvisation is merely the act of solving an equation, and the best improvisers know many ways to solve equations.

Setting the proper environment is vital for your students, preparing them to improvise. Here, you would need to scaffold the learning to pay attention to:

- Understand pulse and meter, making sure the body knows this first before transferring it to an instrument or voice

- Modelling and practising improvisations over a solid and reliable backing track/groove, where students can dip in and out of performing/devising without the fear of getting lost

- Peer support: avoid setting students up to practice improvisations alone. Students can always go to work individually once they feel confident doing so, e.g., for GCSE compositional work.

- Modelling how a change of musical element can alter the improvisation, i.e., a change of pitch, direction of melody (ascending and descending)

- Reliance on rhythm and phrases. Leave gaps or ‘thinking time’ in the improvisation and encourage repetition of rhythms as a way of recycling one idea into another

- Mistakes are part of the process. Frame students’ improvisations as demonstrating equations whilst also showing the workings out

(Wright, 2023)

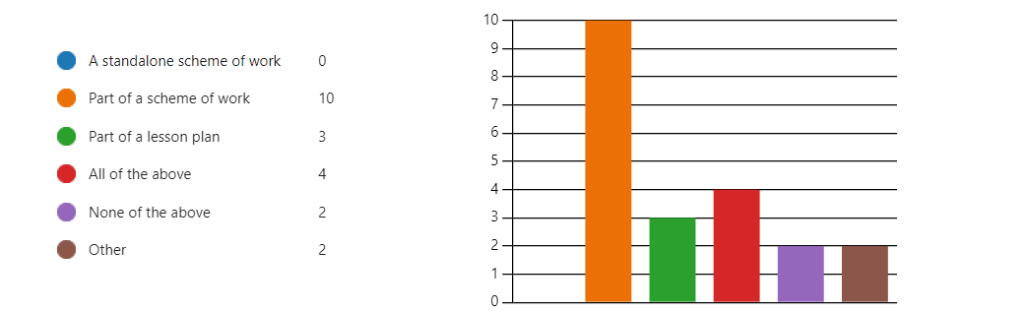

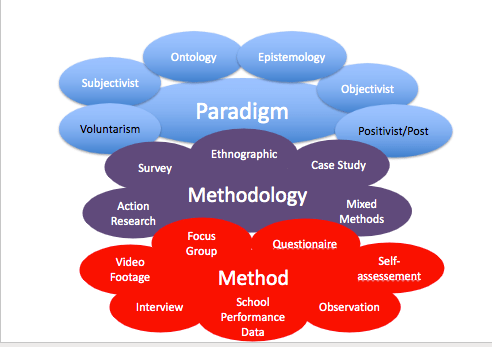

One method that I have used comes from Tim Palmer, who devised improvisation stimuli based on the ‘Solid, Liquid & Gas’ method, which, in his words, promotes ‘dialogic pedagogies that are student-centred, relational, socially transformative and that support empathy for alternate voices’ (Palmer, 2023.40). The alternative voices can be interpreted as support for SEN/neurodiverse students and the plan can be taught as part of a scheme of work or as individual lessons.

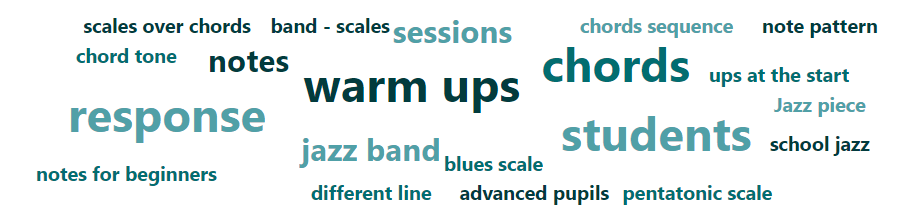

How I used Palmer’s method mainly focused on starter activities for my KS2 students, with ‘Solid’ representing improvising repetitive rhythmic patterns through body percussion or hand percussion, changing only as the rhythm fades out. For ‘Liquid’, this involved using ‘gesture-led’ (conducting) by ushering in different ‘waves’ to the shore, the waves being other students’ improvised parts which overlap with one another, i.e. students are free to move ‘outside the chosen mode to generate harmonic variety’ (Ibid, 45-46). For ‘Gas’, I used numerical melodic patterns ‘designed to represent gases dispersing into the air from a confined space’ (Ibid, 47). Starting on the 1 (1st, students would then add more notes from a scale to expand their improvisations. We began with the pentatonic scales (black keys, major and minor), then moved to major and minor scales. I understood Palmer’s vignettes to be open to interpretation, which, on reflection, helped my SEN students make music accessible, reduce reliance on text or musical symbols not yet understood, and create space for students to explore music and use their imaginations.

Palmer, 2023 49

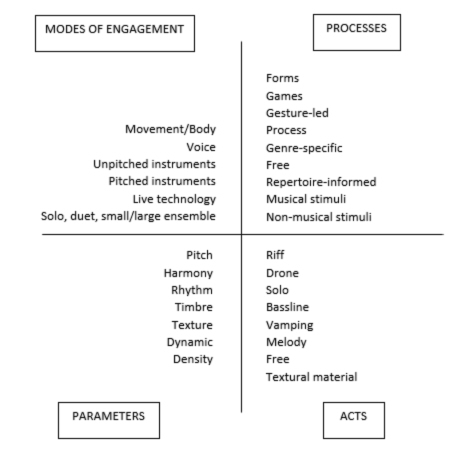

Palmer separated his improvised method into the model below:

Ibid, 46

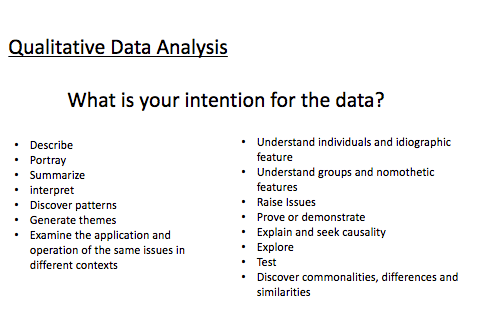

I reflected after each lesson on how students engaged with Palmer’s method, how I structured activities, and which outcomes I targeted. Some factors were beyond my control; students often switched engagement styles or shifted focus from melody to rhythm, such as turning a keyboard into a drum kit. Over time, I learned to accept these variations. Neurodiverse/SEN students absorb information in their own unique ways—often different from non-neurodiverse students.

Support for your high-ability/confident students can also utilise music improvisation; they may already be improvising naturally. Referring to monotrophism, the process of learning improvisation will naturally require concentration and immersion in the minutiae of how it all works. I recommend sign-posting your students to specific musicians and challenging them to learn their language carefully. ‘How does Stevie Ray Vaughn’s vibrato technique differ from John Mayer?’ ‘What do you notice about the rhythmic phrasing of Chick Corea?’

If your students are not drawn to musicianship, use what they already know and build on it. ‘I notice you always start your improvisations with long notes, how about playing shorter notes first?’ ‘You like using the black keys on the keyboard, don’t you? Ever wondered what one of the white keys would sound like if you included them?’ (a trial-and-error method here; you could nudge students towards using B, C, and F, or highlight chromatic passing notes).

This is somewhat autobiographical for me. I remember not knowing anything about music theory in school, and I could just about read tablature. I could pick things up incredibly quickly by ear and internalise them to the point that I could play musically correct parts while demonstrating the details of who I was mimicking. I knew so much about music theory before even knowing what music theory was! Lessons were, as in the 90s, not as diverse regarding adaptive learning as they are today so music lessons focused on notation I could not read (I could not read properly anyway), music I did not understand (If it was not BB king or Offspring, then I would switch off) or practicing with fellow students who could not play (I would learn the part from the teacher, then get frustrated as to why my mates could not do the same). It was much later that I knew the theory that I could put all the pieces together, but I wish I could have done it sooner; another trait of neurodiversity: the feeling of regret mixed with a bit of embarrassment.

There may be a thought as to whether music can help neurodiverse/SEN students learn actually mean, can music help neurodiverse/SEN students behave more in a non-neurodiverse/SEN way? The challenge we face when planning for all learners is the time required, the considerations for all learners, and the pressures from our institutions to show results within their frameworks. We also need to factor in behaviour for learning aspects, and the more demanding our students needs are, the more challenging they are for classroom management and our energy levels. My model of using music improvisation I feel is akin to an adaptive learning framework. I plan my lessons for the baseline of learners but allow for freedom within what is learned via improvisation. No extra planning needed, just giving students my permission to interpret what is learned in their own way, whilst putting in gentle scaffolding to ensure what is being improvised still fits within the lesson objective. This is more so for ADHD students, as they may produce multiple versions of the lesson objective and forget what they created (depending on the type of ADHD, of course). Autistic students, by and large, like the familiarity of structure and avoidance of change or extension tasks, unless one can communicate the benefits of these changes, which are mood dependent. Improvisation can be effective for students with Autism, more so when devising/composing. Still, it becomes a problem when performing, especially when students become dysregulated.

How music improvisation could benefit our neurodiverse students is a research topic I really want to develop, not only for my classroom practice but also because I feel it is important and perhaps still to be discovered, with the potential it may have for our students.

REFERENCES

Berliner, P. (1994). Thinking in Jazz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borgo, D. (2007). Free Jazz in the classroom: An ecological approach to music education. Jazz Perspectives, 1(1): 61–88.

Hickey, M. (2015). “Can improvisation be ‘taught’?’: A call for free improvisation in our schools. International Journal of Music Education, 27(4), 285–299.

Kanellopolous P. A. (2011). Freedom and responsibility: The aesthetics of free musical improvisation and its educational implication– A view from Bakhtin. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19(2), 113–135.

Overy, K. Norton, A. Cronin, K. Gaab, N. Alsop, D. C. Winner, E. Schlaug, G. (2004). Imaging Melody and Rhythm Processing in Young Children, National Library of Medicine

Philpott, C and Cooke, C (2023). A Practical Guide to Teaching Music in the Secondary School. Second edition. Routledge Teaching Guides. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, (Palmer, T), p.39, p.43-49

Shmerling, R, H (2024),‘Right brain/left brain, right?’health.harvard.edu

Walduck, J. (2024). Improvisation Pedagogy: What can be learned from off-task sounds and the art of the musical heckle? British Journal of Music Education, 1-11. Wright, M (2023), Teaching Music Improvisation