In this series, I will present parts of my dissertation, ‘What strategies, activities and methods would help develop the teaching of music improvisation in UK secondary school education?’. I aim to give you insight into my improvisation research by informally presenting my findings, opinions and thoughts. It may start a discussion of the justifications, merits, and advocations for music improvisation or completely put you off and double down on why improvisation should be left out of music education. Either way, I believe it’s a meaningful conversation.

Ethics and Acknowledging Biases

For the first part of the results, I surveyed twenty-two participants via social media through Twitter (X) and Facebook posts. All were working in UK education.

All interview participants, including those transcribed, come from a jazz background. This was not by design but was chosen based on recommendations, availability, and participant’s willingness to partake in the project (a consideration as a bias given the relevance of the research for genres outside of jazz). Therefore, my questions for the survey and interviews did not mention anything genre-related or any reference to jazz music, and it would be at the discretion of the participants to refer to genres they associate with improvised music.

Verbal and written language was also considered, ensuring not to colour or distort responses. Use of language connects ‘our research to audiences’ (Leavy 2017, 29); any reference to jazz vernacular, such as slang terms for describing musicianship, will in some way be translated into a ‘mutually understandable language’ (Ibid) in order not to alienate the reader from a different musical background.

Subject knowledge and research expertise needed to be evident when interviewing and surveying participants, as was communicating with open, friendly and non-judgmental personality traits to enable access, empathy, rapport and trust with self-conducted interviews. (Cohen, Manion et al. 2011). This was important in bringing out the ‘wholeness’ and ‘integrity’ (Ibid, 296) of participant’s experiences, connecting them with the case study and providing a safe platform to do so, in keeping with an ethnographical representation or construction of their ‘social reality’ (Leavy 2017, 145).

How does the research design represent or construct the reality of secondary school improvisation experiences? Paying attention to one’s reality/construct and contrasting with the participants, both qualitative and qualitative data, would be a start, as would comparing the ‘validity, reliability and representativeness’ (Ibid) of responses with the literature review and other results to assess the quality of strategies, activities and methods.

Ethical considerations regarding informed consent were also paramount to the clarity of research or a detriment to the methodology as ‘the more participants know about the research, the less naturally they may behave’ ergo, ‘naturalism is self-evidently a key criterion of the naturalistic paradigm.’ (Cohen, Manion 2011, 228) A possible contention of participants being aware of the nature of research and freedom to express opinions of the methodology could be participants own bias for/against music improvisation in secondary schools or embellishment/exaggeration of their strategies, activities and methods, thus making it hard to control the phenomena that is being researched. That is why my survey data was carefully scrutinised to avoid objective, personal comments, and interviewees must be given opportunities to demonstrate their input by playing what they think works for music improvisation.

Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, Keith Morrison, and Richard Bell. 2011. Research Methods in Education. [Electronic Resource]. 7th ed. Routledge, p.228-229, 289-296

Leavy, Patricia. 2017. Research Design : Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. Guildford Press, p.5-10, 27-30, 129-148

Results from Survey Questionnaire

Background/Training

36.3% learned improvisation in their musical training/background, which decreased to 27.27% when training to be a teacher.

Figures show that despite a low percentage, 86.3% teach improvisation as part of their curriculum, with 45.45% teaching improvisation as part of their co/extra-curriculum. 9% of teachers with training/experience do not teach improvisation in their curriculum but teach it in extra/co-curricular.

Definition of Improvisation

Teachers from an improvisatory background (36.3%) defined improvisation using themes such as ‘in the moment’, ‘play’, and ‘collaboration’. 13.6% used Western musicianship terms to describe improvisation, and 2% referred to ‘learned knowledge’. All respondents used the terms ‘in the moment’ and ‘on the spot’ in their descriptions.

63.6% who identify as having no improvisational background define improvisation as similar to those with a background, adding adjectives such as ‘spontaneous’ and ‘freedom’ and referring to ‘boundaries’, either musical or creative. However, it’s unclear whether this relates to a hindrance or adherence.

Highlighted responses include:

- ‘Improvisation to me is the freedom to creatively express oneself through playing or singing music. I did a music therapy training and so i use totally free improvisation’ (ID7)

- ‘In the moment musical expression which can be either totally free or guided in some way with scaffolding (e.g. agreed chords or limited choice of pitches or rhythms), and which is not written down or notated.’ (ID15)

- ‘Impulsive playing drawn from learned knowledge’ (ID3)

- ‘freeing musicians from the dots is one of the most musical ways into composition a challenge that binds and combines intellect, ear and physical technique very cool and a load of fun’ (ID4)

- ‘Having the tools (chord structure and/or scales) and the freedom to create your own melodic/rhythmic segment to show off your understanding of the music and how to showcase your ability as a performer (like a cadenza) and as a master of your instrument/style of music…’ (ID10)

ID17, who identified as someone with no background/experience in improvisation, playing or teaching, referenced genre (jazz) in addition to spontaneity and ‘in the moment’ as descriptors.

Figure 1: Word cloud taken from questions relating to ‘Definition of Improvisation’.

Rationale for teaching improvisation (linking with strategies/activities/methods)

77.2% thought improvisation helped with ideas for composing. ID10 and ID19 highlight this, with ID10 stating, ‘I find improv helps students then moving onto basic composition in our following chords and melody and know how to use the notes of the chords/follow the chord structure to help improve ideas which are then later refined into “formal” melodies.’ (Q.28)

63.64% felt it helps students to improvise when performing, and 54.5% for developing instrumental skills.

27.2% mentioned blues music as the most popular genre when teaching improvisation.

ID3, ID13, ID15 and ID18 highlight confidence, identity, ownership and self-belief as a benefit of learning to improvise, with a sense of pride from ID18 seeing students supporting each other. ID15 states that as performance and musicianship skills develop, their students become ‘more adventurous’ as students play ‘around more with the formula’.

ID18 stated that teachers must adopt ‘good management of classroom dynamics’ for students to learn improvisation.

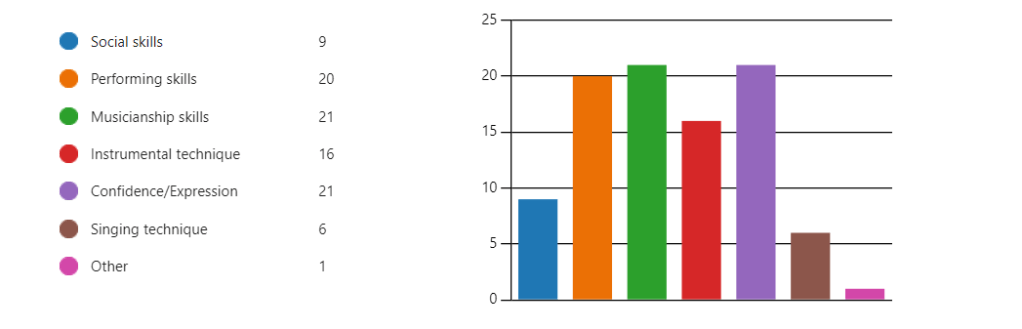

Figure 2: Data to highlight the intra/interpersonal and musical skills that students can benefit from when learning improvisation

Strategies, activities and methods (Curricular)

54.5% reference melody (scales, mode etc.) when teaching improvisation in the curriculum. Due to their inexperience, ID20 uses ‘classroom workshopping’ to teach their students and themselves how to improvise. This includes ‘Circle games, e.g. pass the pulse, or I play/sing you play/sing to model ideas, followed by ‘solos going around the circle’ and ‘modelling ways to build on ideas they come up with, then inviting them to pick an idea and just play/song together.’

ID20 uses backing tracks with a ‘strong and steady groove to help hold the music together’. ID4 uses ‘cells/cycles/ostinati/chord sequences (some kind of groove)’ scaffolded for ‘students focus on rhythmic interest and gradually expand pitch’. ID5 mentions ‘If you can sing it, you can play it.’ regarding philosophy. They highlight singing as a conduit not to be ‘restricted by instrumental skill/availability etc’. This leads to a ‘build up a bank of short riffs (if teaching blues/jazz) based on food rhythms. These are then threaded together to increase fluency.’

ID7 uses improvisation for their work in a special school as a ‘sounding board’ by making musical sense of what the students present. I do this either in a group or individually.’ Scales and the use of pitches for improvisation are encouraged.

68.1% engage with strategies/activities/methods for co/extracurricular activities, jazz being the most popular, with 27.2% who use it. Regarding jazz improvisation, ID6 uses a harmonic exercise to ‘write a crotchet chord tone at the beginning of each bar which matches a chord, i.e. E for a C7, etc. I then get students to begin a solo by starting with the chord tone, and they have to play a phrase that leads up to the next bar’s chord tone.’ ID10 also eludes to a similar approach but simplifies this as a “fill the gap” exercise, ‘Give it a different mood / play with the musical dimensions.

Figure 3: Word cloud taken from questions relating to ‘Strategies, activities and methods (Curricular)’

Support for Improvisation

45.4% of responders would like to use improvisation as part of a scheme of work, with 18.1% for co/extracurricular as a part of the lesson plan. 27.7% want to use improvisation specifically for jazz band/ensemble practice. ID22 requested schemes of work to help with planning, and ID5 requested activities to help with string groups (Grade 4 instrument level). ID19 referred to external pressures regarding results at school and would like more time to develop and research improvising strategies/activities/methods.

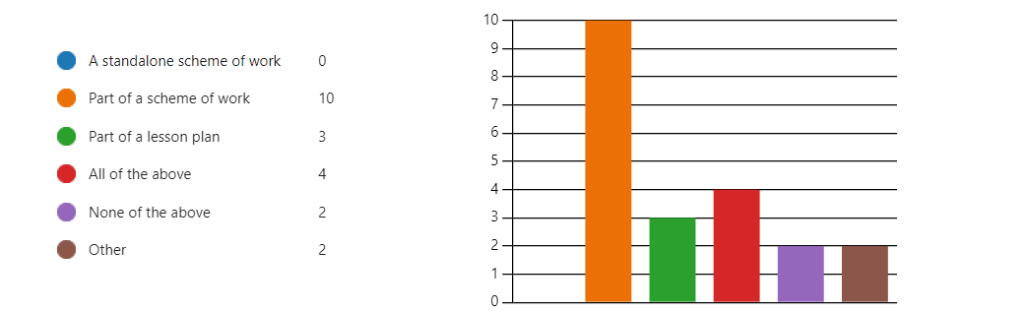

Figure 4: Data to support the participants best use of teaching improvisation in their practice (Curricular)

Issues

27.27% say a lack of personal experience and student’s difficulty understanding improvisation are barriers to learning. The same percentage say they do not come across any issues. 22.7% also state that a lack of improvisation performance, assessing and creating lessons in their curriculum is an issue for their teaching.

ID2 said teachers need to feel comfortable teaching improvising if they do not improvise and recommended training. However, they acknowledged CPD budgets and ‘whole-school issues’ for not teaching improvisation. The type of school and class size are also factors to consider.

ID6 identified the difficulty in planning/understanding and assessing improvisation as a result of a lack of guidance and the feeling of being an ‘afterthought in education’.

ID11, ID9 and ID13 cite a lack of experience and knowledge as an issue (both knowledge and experience) and transfer this onto their student’s opinions of “sounding bad” and being terrified/lacking confidence to attempt it

ID3, ID4 and ID19 see no issues with school improvisation, provided it is scaffolded, with opportunities for students to practise an expectation that secondary school teachers should be able to teach improvisation at secondary level.

Genre, Non-Genre or Both

57% believe that both genre and non-genre led approaches can be used to teach improvisation, with 22.7% believing improvisation can be taught with a genre in mind.

Those who agree with a combination of both genre and non-genre teaching mentioned it is best to start ‘totally free’, then ‘once confident one can start to introduce structures, chords, and specific genres’. ID7, ID8, ID13.

ID11 believes some styles (jazz and blues) should follow their associated ‘rules and traditions’. ID20 believes non-genre helps teaching, ‘creative nature of improvising means that it can be applied to any and every musical genre’

ID6, ID16, ID17 thought improvisation should be taught with genre stated that the history of genre, context, and genre-specific musicianship, ID6, D18, ID22 referenced learning improvisation as a language.

ID17 stated: ‘Pupils need to know about genre and history. Context of genre means students know about it so they can understand the music.’

ID6 stated: ‘Improvisation needs to have context. If you’re playing jazz music but haven’t been taught about compound rhythms then how can you play jazz properly?’