Methodology: How to gather data that represents the current landscape of music improvisation in UK Secondary education

In this series, I will present parts of my dissertation, ‘What strategies, activities and methods would help develop the teaching of music improvisation in UK secondary school education?’. I aim to give you insight into my improvisation research by informally presenting my findings, opinions and thoughts. It may start a discussion into the justifications, merits and advocations for music improvisation or completely put you off and double down on why improvisation should be left out of music education. Either way, I believe its a meaningful conversation to have.

Choosing my methodology was a painstaking process that saw many revisions and misunderstandings on terminology. I felt a bit silly when presenting this in my viva voce! What helped me solidify my approach to the dissertation was this video by Amgad Badewi:

He expertly defined the terminology I needed to justify my rationale and narrowed down what I wanted to find out and how I would get there.

Firstly, is the research aiming to fill a knowledge gap (measured academics, theoretical) OR solve a problem? (applied scientific research). I was initially planning on solving the ‘problem’ with a lack of collectivised music improvisation pedagogy, but to go in with this approach would mean I have the pedagogical tools and academic credibility/authenticity to do it, which I don’t. How about filling in a knowledge gap? That might have legs, as my literature review uncovered methods of improvising but little in the way of secondary school. The sweet spot lies in the middle of the two, and by filling a knowledge gap, I may also solve the problem of a lack of knowledge.

I then proceeded to the definitions of the latter two. Generally speaking, Badewi equated the Knowledge gap to positivist research and problem-solving to interpretivism. Positivism (causal/quantitive/objective research) explores reality through reading and finding information from responses from people; it attempts to find a ‘reality’ of the research. Interpretivism (non-reality) relies on descriptive/qualitative research, which is a bit more focused on what the data presents. (Badewi, 2013)

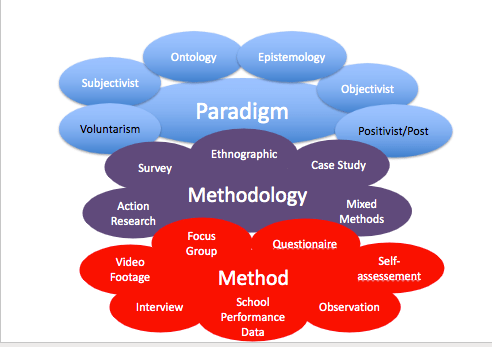

Next up is the research paradigm. What is one’s concept/model of research?

How would the data be processed if my research aimed to fill the gap? Would it be ontological? (a belief/perception about reality (constructivism) no single reality) Epistemological? (interoperating reality)

Figure 1. An overview of how my methodology was created

Science-based? (collect information—propose hypotheses—test hypotheses objectively) (ibid). Much of this decision was based on the data being presented in a way that authenticated improvisation strategies, activities, and methods in their most genuine way and respected the method of improvising itself. Music improvisation is open to interpretation and has many factors that determine outcomes, not just knowledge and memory recall.

After many drafts, I finally had it. The research would conducted as a (drumroll) ’embedded single-case study’ (Cohen, Manion et al. 2011, 291), allowing for multiple data sources data built-in.

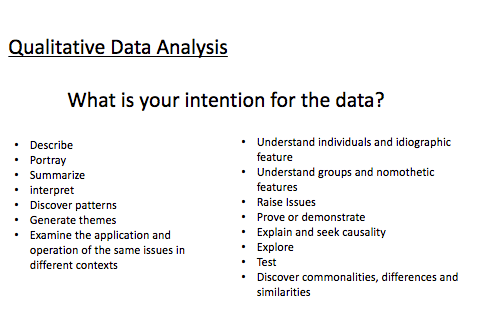

I could not limit my data pool to just one place, so I planned for a mixed methods data collection, using an online questionnaire targeting music teachers and educators experienced with teaching music at secondary education level. Quantitative data would provide a starting point for findings, with qualitative data (interviews) embellishing the quantitive findings. Planned in two stages; stage would be the survey questionnaire, and stage two would be the interviews, including transcriptions from Music Teachers’ Association’ Teaching Notes’ podcast and live interviews with my participants. Both methods would be run concurrently with stage one coded first and then stage two. Data would be paired together to observe patterns, similarities and differences in findings. This case study required me to gather data that was fit for purpose and skilled in probing beneath the surface of phenomena, defined more by the results and findings and less by the methodology used. (Leavy 2017)

Figure 2. Notes from my lecture on quantative data analysis

A Rationale for Research Methods

My thinking was to allow my single case study’s topic to remain narrow but provide a comprehensive method for collecting my data. The qualitative data would favour the quantitative, with the latter supporting the former. I needed to be flexible, too, as the initial idea of how my research would present improvisation in secondary changed frequently. This meant the case study could present data as descriptive (‘providing narrative accounts’) (Cohen, Manion et al. 2011, 291) and help ‘identify or attempt to identify the various interactive processes at work, to show how they affect the implementation of systems and influence the way an organisation functions.’ (Bell 2014, 12) (Flyvbjerg, 2006). In this case, the implementation comes from embedding improvisation in secondary education.

Participants’ experiences played a crucial role in validating the research and survey data, determining what is known and what can be learned by accessing the knowledge base of survey participants and interviewees, with a level of authenticity, I.e. music educators with lived-in experience of teaching secondary school music improvisation (Cohen, Manion 2011). In theory, this should have enabled the reader to recognise idiographic ideas presented by the case study, not ‘abstract theories or principles’ (Ibid, 289), letting the ‘observational evidence’ (Chapman & McNeill 2005, 98) present itself. Collecting multiple data had to be bound by commonalities and general information in current improvisational research and those who participated. Limiting what one finds in the data will bind this with identifying the phenomenon of the project’s research and serve as the project’s boundaries, defined as:

• Cases will have boundaries which allow for definition.

• Cases may be defined by an individual in a particular context.

• Cases may be defined by the characteristics of the group (or individual) (Hitchcock and Hughes 1995, 319)

This is also backed up by Yin, who also references similar boundaries of research. These include:

- Specificity of case study (research) questions to keep within the boundaries of the research topic.

- Constitution of the case study (the research’s principles and propositions, not to be confused with ethics). This includes basing the research on a ‘real-life phenomenon.’

With additions regarding:

- Linking the data back to the initial research questions with analysis and triangulation

- A ‘criteria for interpreting the findings’ resulted from the case study. Interpreted in a way which is robust and can withstand scrutiny. (Yin, 2009)

Interviews were semi-structured, following a template of questions tailored to fit the interviewee’s experience and job role, i.e. questions regarding strategies, activities and methods for the peripatetic piano teacher to focus on individual students. Structuring questions for each interviewee. Semi-structured interviews allowed for a more conversational approach. They allowed participants to express thoughts that may be unrelated to the topic but provided other avenues of research that could be useful. (Bell, 2014)

Qualitative data outcomes would have a different relationship with qualitative data due to changes in interviewee’s experiences, beliefs and views (Hitchcock and Hughes 1995). In essence, it captures the participants’ ‘constructions of the world’ (Ibid, 324). The participants’ experiences, knowledge, and ambitions for improvisation were triangulated through the researcher’s lens, meaning that when I changed focus, the qualitative data changed, too.

The following types of triangulations were identified:

- Data triangulation – data collected over a period from more than one location and from, or about, more than one person

- Investigator triangulation – which involves the use of more than one observer for the same object. This can also involve member checks. That means taking data and interpretations back to the subjects to ask them if the results are plausible.

- Theory triangulation – which involves the use of more than one kind of approach to generate categories of analysis.

- Methodological triangulation – the use of more than one method of obtaining information within a data collection format.

(Ibid)

Things to Consider

Would my methodology fail to capture the true nature of secondary school improvisation? Or would the methodology benefit secondary school educators by standardising a topic for a cohesive pedagogy? Supposing my methodology explores what is known and/or effective and allows the reader to modify and enhance their practice, any notion of inconsequential research must be disregarded (Leavy 2017). By regulating the benefits and limitations of my methodology and ‘critically informed opinions’ (Ibid, 7) around what is effective in secondary school improvisation, I hoped to collect information that generated a model of recommended improvisation strategies, activities and methods in secondary schools.

Critics of the case study approach draw attention to several problems and disadvantages. For example, some question the value of the study of single events and point out that it is difficult for researchers to cross-check information as a result of data’s ‘limited generalizability’ (Cohen, Manion et al. 2011, 294) and be dismissive of other similar case studies (Bell, 2014) (Cohen, Manion 2011). By designing the methodology, we expect the data to change the research path, move away from fixed research criteria, and be open to other case studies. Another argument against it is based on the focus and longevity of the case studies. Yin warns of choosing case studies that are ‘done about decisions, about programmes, about the implementation process, and about organisational change.’ (Yin 1994, 137), as none are ‘easily defined in terms of the beginning or end point of the case’ (Ibid). Hitchcock and Hughes also agree that a case is not worth pursuing if a boundary is indeterminate (1995). You can perhaps see how researching improvisation falls into this trap; my counter-argument to this was my ambitions to continue my case study by widening the data collection to develop a bigger picture of improvisation in secondary education for as long as I’m prepared to collate stories, opinions, and other research that remains within the chosen case topic’s limits (Yin 1994). The potential for this research development can only be for the gain of secondary education.

Ethics and Acknowledging Biases

All interview participants came from a jazz performance/improvisational background. This was not by design but based on recommendations, availability and participants willingness to be in the project. Therefore, the questions for the survey and interviews did not mention anything genre-related or pertain to any reference to jazz music. It would be at the discretion of the participants to refer to genres they associate with improvised music. I was aware that use of jazz vernacular could narrow my research to a specfic audience (Leavy 2017), so any reference to slang terms for describing musicianship, was translated into a ‘mutually understandable language’ (Ibid) in order not to alienate the reader from a different musical background.

I needed to show my subject knowledge and research expertise when interviewing and surveying participants, whilst communicating in an open, friendly and non-judgmental manner to enable access to information, empathy, rapport and trust with my interview participants (Cohen, Manion et al. 2011). This was important in bringing out the ‘wholeness’ and ‘integrity’ (Ibid, 296) of participant’s experiences, connecting them with the case study and providing a safe platform to do so, in keeping with an ethnographical representation or construction of their ‘social reality’. (Leavy 2017, 145)

How did the research design represent or construct the reality of secondary school improvisation experiences? Paying attention to one’s reality/construct of, contrasted with the participants qualitative and qualitative data, aware of its ‘validity, reliability and representativeness’ (Ibid) of responses. This also included the literature review and other results to assess the quality of strategies, activities and methods.

A possible contention about participants being aware of the nature of research and having the freedom to express opinions could be participants’ bias for/against music improvisation in secondary schools or embellishment/exaggeration of their strategies, activities, and methods, which made it hard to control the research phenomena. The likelihood of this happening was down to the trust I had in participants answering honestly and accurately, afterall it wasn’t as if they stood to benefit anything personally from embellishing their responses.

Bell, Judith. 2014. Doing Your Research Project. [Electronic Resource] : A Guide for First-Time Researchers. Sixth edition. Open University Press, p.10-14, 178-192

Chapman, Steve, and Patrick McNeill. 2005. Research Methods [3rd Ed.]. 3rd ed. Routledge. 98-101

Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, Keith Morrison, and Richard Bell. 2011. Research Methods in Education. [Electronic Resource]. 7th ed. Routledge, p.228-229, 289-296

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12, no. 2 (April 2006): p.219–45, p.219-224

Hitchcock, Graham, and David Hughes. 1995. Research and the Teacher. [Electronic Resource] : A Qualitative Introduction to School-Based Research. 2nd ed. Routledge, p.316-329

Leavy, Patricia. 2017. Research Design : Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. Guildford Press, p.5-10, 27-30, 129-148

Merriam, Sharan. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. Jossey-Bass, p.169-170

Welch, Graham F., Adam Ockelford, Sally-Anne Zimmermann, Evangelos Himonides, and Eva Wilde. 2016. The Provision of Music in Special Education (PROMISE) 2015.

Yin, Robert. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, Canada: SAGE Publications, p.27

Yin, R.K. (1994) Designing single- and multiple-case studies, Nigel Bennett, Ron Glatter, and Rosalind Levacic, Improving Educational Management: Through Research and Consultancy. 1994. p135-156