Hello everyone,

My word its been a while since I last posted! Probably due to focusing on starting the school term 20/21 and working on my MA Teaching Musician work, either way I neglected to produce any content for my site…can you forgive me?

If you can I guess you’ll continue to read on, and I’m glad you are because as I have handed in all assignments for Block A (currently awaiting grading) and find myself having free time over weekends, but rather than waste it on unlocking all characters from Streets of Rage 4 I’d thought I’d make myself useful and share some new founded knowledge as I reflect on a stellar year at Trinity Laban as well as new skills/experiences learned in my teaching practice.

Now i’m not promising to regularly update as my MTA colleague James Mannwaring does on his influential teaching blog (James, if you’re reading this, collaboration my friend?) nor will I promise to not get distracted by SoR 4 afterall, that Blaze character doesn’t unlock itself huh? But I will make a bigger effort to you to share what I have stored in my head and the pages of research (literally, a few pages) in a handy and, hopefully, informative read for you. With that being said I present to you an assignment come manuscript that I completed late last year, adapted from my Teaching in Practice 2 assignment which was to research creative group collaboration. I hope it provides an insight into how quickly and efficiently we music teachers had to adapt out practice to the current climate and what we must pay attention to for a post- COVID music education landscape.

*Identities, gender and background and other relevant data has been withheld due to anonymity of school and students. This blog has also been edited to fit the theme and narrative of this post.

………

This paper explores how using cloud-based software apps (both music and non-music based) provided students with practical music lessons whilst maintaining social connection and interactivity with each other during the lockdown. The paper will also explore how new remote teaching pedagogy can work in combination with pre-COVID methods to create music, with a focus on the following:

- Explore how a constructivist philosophy works within a remote learning framework (The Online Classroom)

- Understand how ‘audiation’ is used to model, support and enhance student’s creation of work (The Process)

- Observe how ‘explorative talk’ works with audiation when using formative assessment (Assessment and Communication)

By exploring the implications (negative and positive) associated with remote learning in lockdown and teacher training, implications effect on future pedagogy, COVID’s change in perceptions towards creating music and justifications of music in a post-COVID curriculum, this research aims to provide insight into how music educators adapt to a new education landscape for the benefit of students and the subject.

Keywords: online learning; remote learning; remote teaching; digital pedagogy; COVID; music education; DAW; digital audio workstation; Soundtrap; Microsoft Teams; online music education

Case study background

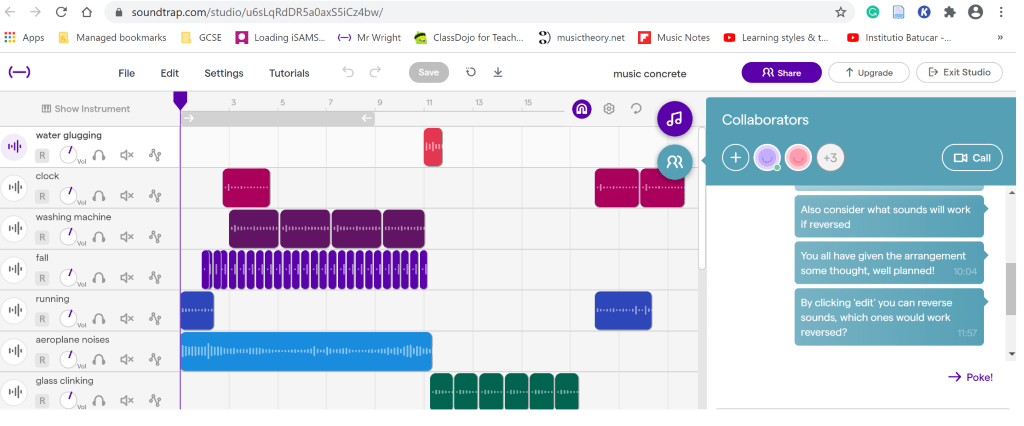

The research shall focus on a Year 7 class*. All students have previous experience using Soundtrap (a cloud-based DAW). This included techniques such as MIDI sequencing, looping and layering parts and for some, use of effect plugins and track automation. The choice for using Soundtrap, other than familiarity and being cloud-based was that students found its user-friendly interface, tutorial videos ease of creating music and collaborating very efficient. The dialogue box and ‘virtual keyboard’ were the most significant selling points, making communication instant for all (Dunbar, 2019) as well as eliminating the need to have external hardware such as an audio interface and MIDI keyboard/controller to use the app, which none of the students had access to at home.

Students task was to create a piece of music in the style of/borrowing from Musique Concrete (Concrete) and present their compositions at the end of the term. How they capture sounds recorded via mobile phone, utilise home surroundings and household appliances to form the basis of their compositions and arrangement; students also had to demonstrate the use of sound editing. Creating the music on Soundtrap and using interactivity of Microsoft Teams (MS Teams) provides the online classroom space for registration, practical work and general interactivity with students.

Due to its relative ease of creating, abstract qualities and no reliance on functional harmonic knowledge to compose, Concrete seemed to be an exciting choice to make, albeit leftfield. There were concerns about its dissonant and abstract qualities though, the concern being students could accept this as a credible way to make music, so rather than focus on stylistic character, encouragement of creating as a group, exploration/experimenting with sounds and emphasis of creating a piece of music (or art) was promoted. Given the class had no immediate access to class musicianship resources, or a teacher to quickly demonstrate any questions relating to this, the choice to compose in the style of Concrete also made the collaborative composition process easier. Planning proved to be problematic when factoring in how to model specific musicianship skills related to melody, harmony and rhythm in the scheme’s timescale and allow time for composing. Besides this, prior learning focused on using these musicianship skills, so a break from the norm was considered better for students to re-engage with making music using different methods.

The Online Classroom

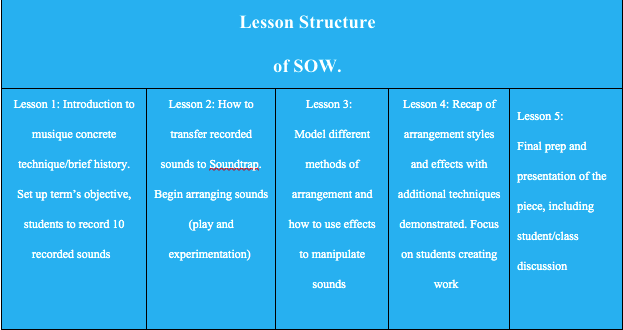

The overview of this term’s lesson structure (five weeks) and content is as follows:

Figure 1: Taken from the authors ‘Making Music using Recorded Sounds’ unit plan

The choice of using a constructivist approach, defined as ‘creating learning conditions that engage students in active learning and in using higher-order thinking to foster personal meaning making.’ (Johnson, 2018, p.186). Furthermore, working to identify how practices are built based on inter and intrapersonal skills, experimenting, evaluating and conclusions which are directed by the students (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2003) was one of necessity due to lockdown but also for students organise their roles to create their learning environment. Dobson (2019) also alludes to this approach when discussing collaborative work, ‘collaborative music composition requires them to navigate various equipment and process situations, while simultaneously building a shared understanding about what it is that they are creating together’. (p.2)

The constructivist approach felt logical to use considering the circumstances, though for it to work, creating a positive classroom environment is vital. Biasutti (2015) writes ‘students’ satisfaction with online activities relates to their perceived levels of collaborative learning…’ citing factors such as ‘individual accountability, familiarity with team members, commitment toward quality work, and team cohesion’ to be necessary for the environment (p.50).

Using Soundtrap for remote learning also has its advantages. Bauer (2014) states ‘While technology may be a gateway to involve non-traditional students in school music programs, those who are already part of school music classes and ensembles can also benefit from using technology to facilitate the development of their musical creativity’ (p.46). A reasonable statement to make as ‘non-traditional’ students will benefit from using the app in a home environment and have freedom and control to create music to be altered and enhanced at any time, something which can be lost when performing live as inconsistency of musicianship with non-traditional students is often the case.

The Process

The process (a method students choose to create) relied on student groups to actively engage with each other to arrange their Concrete composition using guidance from the teacher. Two methods were demonstrated in these lessons, layering (music-based: similar to an EDM based arrangement, but not specific to bars or meter) and shape (visually based: using the recorded sounds to create a shape of the arrangement, including the colour of parts).

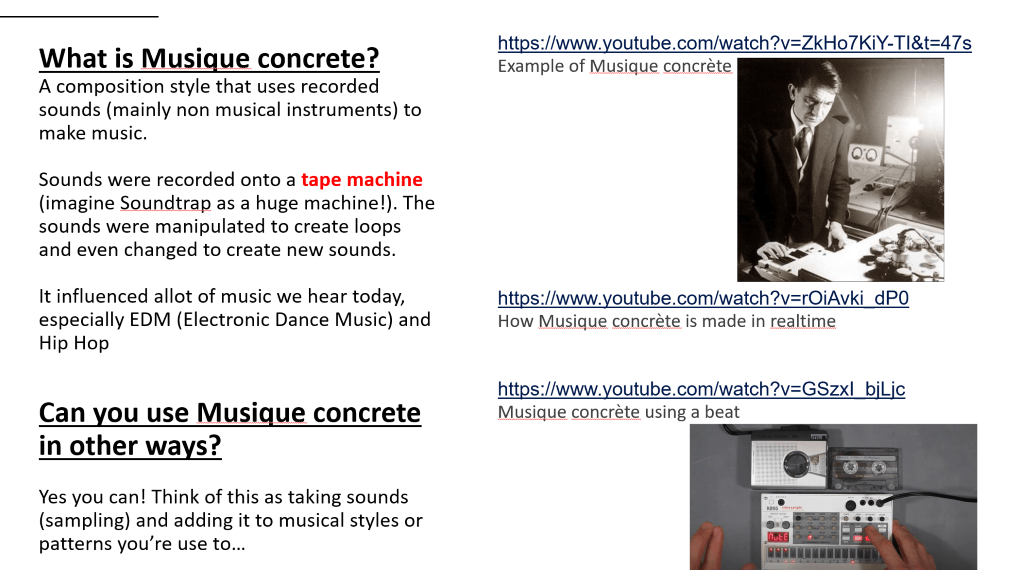

Figure 2: Taken from the authors ‘Making Music using Recorded Sounds’ lesson 2 and 3 PowerPoint

In overcoming the issue of modelling and getting students to understand how they can create compositions, audiation was used to communicate with students (Gordon, 2012 & Bauer, 2014), particularly pertinent when making Concrete.

By using Gordon’s audiation philosophy at the start of lessons, as defined by creating meaning from sounds based upon knowledge and making choices using discriminative and interference learning (2012), students would be more methodical and selective with recorded sounds to the benefit of creating musical ideas (Bauer, 2014). However, this opinion is at odds with what students are tasked with doing in lesson 1 (The contrary being students are actively encouraged to explore and randomly pick sounds to use for their compositions).

The ability to think ‘musically’ when choosing sounds was used when advising some students to pick sounds, with such questions asked to highly able students:

- “What references to musical instruments can you hear when you chose your sounds?”

- “Does a particular sound remind you of a song or instrument?”

Or to all students:

- “When recording sounds, see if you can pick sounds that are low, middle and high pitched.”

Audiation would play a crucial part in modelling sound manipulation, particularly useful in lessons 3 and 4 as students progressed using this to develop their compositions. For instance, demonstrating that adding lots of reverb (wet) could create the sound of being in a church or tunnel, adding distortion to replicate something on fire, or adding chorus with full rate and depth to make something sound like its underwater is more natural to model if one was to use audiation skills. By getting students to experiment with sound manipulation, the aim was that students would make their own opinions or predict what effects may alter the sound (Gordon, 2012).

In Swanwick’s flow chart (Swanwick, Teaching Music Musically, 74, figure 5) audiation works to create music and feed into choices when creating/manipulating sounds. As Concrete forces students to create musical meaning from abstract sounds, students are forced to justify the choices they make but not for the sake of assessment criteria. The expectation is that students will make significant strides in their work when exploring sound manipulation and arrangement, evolving into highly creative compositions.

Assessment and Communication

Use of ‘Exploratory talk’ in conjunction with audiation will be relied upon when communicating with student groups. Dobson (2019) writes that by becoming too demanding and controlling of the learning experience, ‘critical and constructive’ engagement with ideas will not flourish. (p.13). Modelling and justifying the reasons behind the use of specific sounds is crucial in understanding how to make music with recorded sounds—showing that Concrete’s method of music-making is unconventional (in comparison to previous work), but valid.

Figure 3: Screenshot taken from lesson 1 ‘Making music using Recorded Sounds’ PowerPoint. This refers to Contextualising Concrete being an acceptable composition method, links and fusions with other genres that use the methods.

The aim is that students would be drawn to their conclusions and reasons for their work and more importantly, feel free to create something in their image. Communication ranges between explaining using exploration-based feedback:

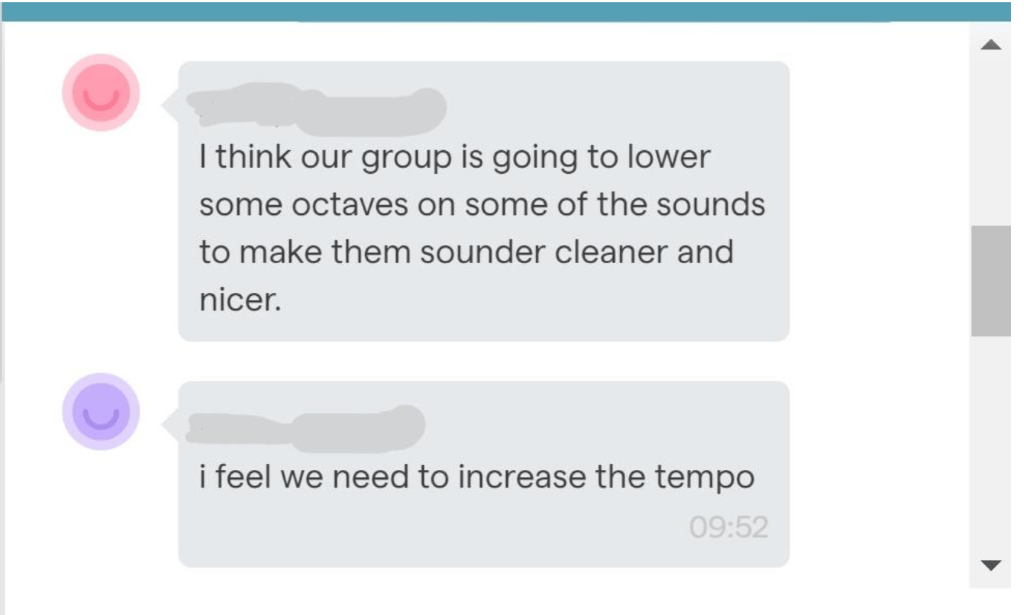

Figure 4

Figure 5

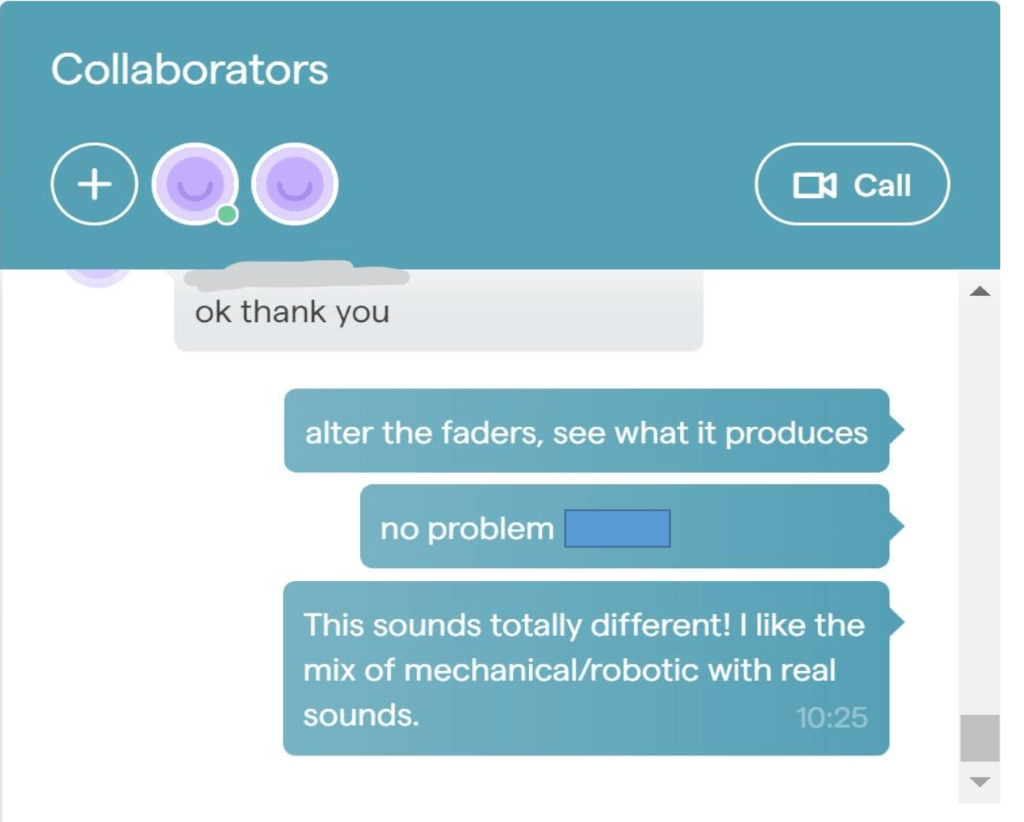

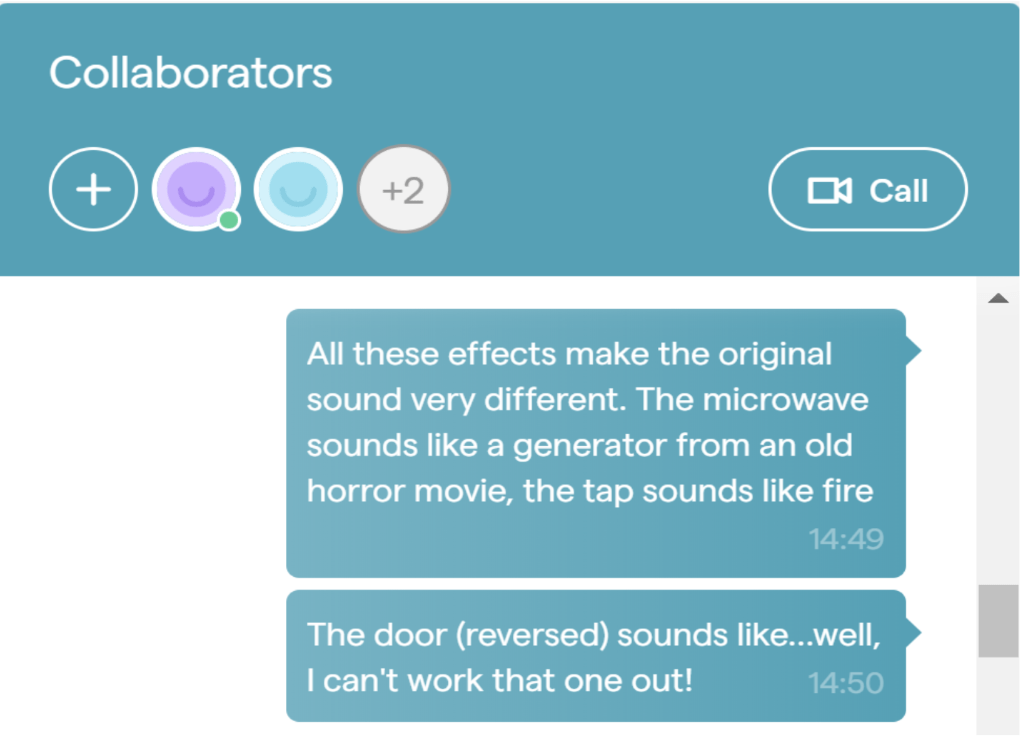

Use of audiation:

Figure 6

For musicians, encouragement for students to use music theory-based language (Swanwick, 1999):

Figure 6: In response to a question regarding an issue with recorded sounds clashing pitch-wise

Formative student feedback was positive, sincere and encouraging (Bauer, 2014) not to make comments misconstrued as demeaning, negative or not helpful:

Figure 7

Feedback was given in short and frequent bursts. In previous online lessons, too much technical details were given to students, and a majority of this overlooked. By referring to lesson criteria, students can make decisions based on what they wanted to include in their work and gain confidence heading in the right path (Bauer, 2014).

Results

Groups presented their compositions in the last lesson of the scheme and term, before this at around the 4th lesson, one student asked if their group could use imagery/video for their piece which was consented. After deliberation, students were offered the use of images to enhance their compositions. Thanks to this amendment, groups changed their approach to the process, making it more in line with examples modelled at the start of the unit.

Compositions that showed a high level of musicianship, as defined by the following:

- Creative use of sounds (looped sounds that resemble some form of musical instrument or melody, harmony or rhythm)

- Well-organised structure and use of sounds (sounds were layered demonstrating mono, homo or polyphonic texture and structure referenced binary, ternary, strophic or rondo form)

- Creative use of sound manipulation (nondestructive editing such as reverse or time stretching)

- Creative use of effect plugins (adding effects to represent the image in some way or technically enhancing the sound)

Groups that demonstrated these points were able to justify their choices regarding arrangement, sound choice and manipulation and elaborate why the images related to their compositions. In some examples, individuals explained the use of stacking effects and how it resembled the image, both visual and audio. This happened when a student described how using distortion and chorus replicated the image of a house burning next to a lake, with the distortion effect representing the fire and chorus representing water.

Groups 2, 7 & 11 also spoke about the sounds directly relating to the images but not in explicit detail as the other groups mentioned. Group 7 explained how their ‘eerie’ sounds captured represented the ghost figure and dark atmosphere related to their picture with the 2nd part of piece intending to be a leitmotif of the ghost, and group 11 described the metallic sounds mixed with effects (reverb and delay) with the horn recording, all replicating sounds heard in a freight train yard.

Groups who produced satisfactory efforts, demonstrating some use of sounds, structure, sound manipulation and effects or demonstrated basic composition/programming skills managed to link compositions with matching images (where applicable) and when critiqued, only needed to make a few adjustments to the number of effects used, arrangement method and sound editing techniques to improve the grade.

Out of the groups, four (11, 7, 4 and 12) contained students who take music lessons or contribute to the music department and made up the majority of students who produced highly creative compositions. A surprising number of groups (those who did not have musicians within them) still managed to produce examples that were musical/artistic, in particular, groups 1 and 2 managed to capture the imagery of a tropical beach with their recorded and sampled sounds with success.

Discussion

The design of this online classroom suffered from little preparation time in comparison to planning for a ‘normal’ classroom lesson. Given the circumstances, it would be unfair to be too self-critical as ‘online learning has many interconnected components and many factors must be considered’, making it ‘hard to provide a straightforward checklist or recipe to follow’ (Ally, 2008, p.134). That said, digital pedagogy is much the same as non-digital, which is ‘essentially personal and cannot be standardised’ and still requires successful educator understanding ‘the need to vary instruction for the diverse range of students in her (their) classroom’. Where new and existing ‘tools and strategies’ can be ‘implemented to help support and encourage students to learn in the online environment through offering personalisation’ (Johnson & Lamothe, 2018, p.229). In hindsight, the components and factors Ally mentioned could have been handled with the same mindset for planning a face-to-face lesson and personalising the lessons; instead, the learning experience was personalised more to fit the remote lesson narrative.

The remote experience did provide valuable insight in how one’s planning of scheme, delivery and monitoring of progression should be adapted in future, with more freedom given to how students interoperate the learning, less focus on the technical limitation’s students shows and whether students have completed tasks compared with the qualitative outcome. Although issues related to the remote teaching experience were expected, these issues could have been anticipated. These include a clearer checklist of sound manipulation devices to use (including effects), links to videos that further prove how they can be used, and more time afforded to the modelling of arrangement either as a class or for specific groups and support in selecting and organising recorded sounds. Directly recording from device to Soundtrap was thought to result in poor audio quality but turned out to be irrelevant. Students found this process easier and added sound manipulation techniques which obscured the sound.

Regarding MS Teams for peer reflection and group discussion, more could have been done to include the thoughts and opinions of the case study group. Due to time constraints and prior planning to make the most of the lesson time, with lesson 2 benefitting from a more straightforward process to upload recorded sounds onto Soundtrap, a meaningful discussion session could have taken place.

Groups posted their assignments onto Teams and after playing their pieces to the class, engaged in a teacher-led discussion about it, if students felt shy or uncomfortable speaking, then they were permitted to post a comment in the ‘General’ chat. The benefit of this peer feedback was that it allowed students to hear each other’s work and allowed them to talk about the creative experience as part of a discussion (experiential). Some students did not engage with this process, and in a real classroom setting it would have been easy to initiate a response, in the remote classroom setting, however, directly asking a student for their views proved challenging as they could ignore the question and switch/mute themselves. There was then, a balancing act in being aware of class interaction with each other and interact with the teacher, making sure to respect boundaries when students communicated in chat boxes with each other but making them feel like the lesson was monitored (Johnson & Lamothe, 2018).

Those who did not fully engage with the lessons (not turning on the camera, contributing to discussions, having ‘wifi issues’ and so on) produced less satisfactory work than those who were moderate to highly interactive with the lesson. This issue could have been a result of a poor social connection with both the teacher and classmates (Biasutti, 2015). By the time students started the scheme, they had several months of online learning and time spent away from school and their friends. Speaking from experience as a form tutor during this time, students reported feeling isolated, lonely, frustrated and angry at not being able to be part of the school community and having lessons in person. Despite the best efforts of the school and teachers to create a community, a sense of fatigue and overload of lesson format could have contributed to the lack of engagement, as well as having oneself on camera and the feelings of self-consciousness and shyness that comes with knowing that interactions will be visible. The difficulty of connecting socially in remote learning perhaps proved too much for some, who may have longed for real human connection, but the use of Soundtrap and Microsoft Teams provided surrogate interactivity for students and enabled them to communicate and create music synchronously.

With the help of Swanwick’s table (Swanwick, Figure 4 The functions of assessment, 72) the filtering-teaching-examining model was used to good effect when discussing group work in summative assessment. This was used to speed up the flow of lessons, give less emphasis on teacher control and tie in with student’s autonomy, demonstrated in work (Examining) assessed by students when reporting back on their process method. This aspect led to students assessing what they had done in comparison with teacher feedback, thus encouraging listening and critiquing skills whilst highlighting good examples of technique/imagination shown; this way of communicating authenticated Swanwick’s statement as ‘assessment in the most educationally important sense of the word’ (Swanwick, 1999, p. 72). By covering the basic composition techniques associated with Concrete, students worked more diligently and focused on creating exciting pieces of work. The learning outcomes were translated into students work and use of strategies, but more importantly, communication/expectations meant students achieved what was intended (Ally, 2008).

Though this case study demonstrated success in using Soundtrap with MS Teams, there are opportunities to research other combinations of cloud DAWs and online workspaces/hubs such as Splice, JamKazam, Avid cloud Pro Tools and Abelton (Reverb.com, 2020) along with Google Classroom or Zoom. The choice of what apps to use should refer to the school policy framework, as was the case for using MS Teams for the case study, choice of DAW though could depend on personal preference, student accessibility in terms of ease of use, lack of hardware needed to use it and affordability. Soundtrap not only demonstrated the latter two’s justification for using but during the lockdown, they offered a free six-month license to schools. The full program, without the free license would have cost the music department thousands of pounds to grant licenses for all of KS3. In regard to cohorts, it would also be worth researching if the use of Soundtrap is suitable for KS2 level though one would expect this not to be the case, certainly for Year 5 and below. An app that may work in this context is Chrome Music Lab’s ‘Song Maker’ which provides a much simpler interface than Soundtrap using a matrix window editor as the main screen with coloured notes to separate the notes on the keyboard, either as pentatonic, major/minor or chromatic scale. Also, Music Lab provides a two-part drum matrix on the bottom of the screen, MIDI and audio recording function and bounce mix facility, all of which provides the foundation for DAW music programming and acts as a platform to use more advanced apps.

Conclusion

As previously mentioned, composing in the style of Concrete provided students space, creativity and interactivity to produce work. The Year 7 class worked in composing a ‘Tribute Song for Key Workers’ in a Pop/Rock style. The template for case study borrowed from this showed this model of remote teaching and planning could be adapted to teach online composition using DAW, providing the framework for remote teaching is covered. The case study/collaborative process demonstrated that if students felt comfortable working with systems set up by the teacher and had the belief that the work was merited, there would be no barriers to engagement and creativity. Working with online classroom limitations meant the teacher’s impact in learning is only as good as the student’s ability to comply and work independently. As well as placing faith in students to build their learning environments which were reciprocated by the teacher’s willingness to trust them; by utilising technology and using mobile devices in tandem with computers, placing confidence to be used as part of their education would be advantageous.

The challenge then is to maintain the momentum gathered during the remote learning period by bringing the best parts of the methodology into an emerging digital pedagogy. It can be achievable, as schools re-opened across the country, strict COVID protocol has been put in place to prevent close contact for long periods and adhere to social distancing guidelines, meaning some departments’ practical breakout space has gone or more likely, the teacher must distance themselves from students in the classroom. The shift towards relying on using music software to safely interact with student’s music making would mean using an online program like Soundtrap in one’s day-to-day teaching. Which would mean being able to edit students work in class at a distance when both can see the amendments on screen, and from a pastoral perspective, allow students to carry on working at home during lesson time providing they need to self-isolate if they are safe and well enough to do so of course.

Music education must be careful though in its overreliance in a ‘tech-saturated culture’ (Bell, 2015, p.45), of communicating a message of ‘possession of music technology is the key to unlocking the hibernating musician within’ (p.45). Traditional means of making and performing music, i.e. access to classroom instruments, was lost due to lockdown, and for the new generation of music students the ‘new normal’ in education should not revolve around using laptops, tablets and computers. Students should still be taught the fundamentals of musicianship and collaboration by developing necessary technical skills that come with learning an instrument (Bell, 2015). This could pose a danger that a lack of idiomatic knowledge for instruments will be lost if they are reduced to purely selecting them as VST patches (virtual studio technology), for example, students would not learn why certain extended piano chords need to be voiced to fit hands for comfortably.

Music educators should be expected to navigate software apps, music notation and DAWs. Training should reflect this either in professional experience/Undergraduate and be reinforced at ITT level. COVID could have pushed schools/institutions to an entirely ‘cloud-based’ music platform if it has not done so already. By creating music over lockdown, students’ reliance on online cloud based apps, benefitted those who would have usually found it hard to learn a topic using traditional instruments. One particular comment made in passing during one of the lockdown lessons reiterated this, (paraphrasing) “Using Soundtrap takes some of the focus of learning an instrument and makes me think about playing music as a whole, not just focusing on my part”, and many students expressed delight in not having to use a keyboard to play parts. Use of technology could now be crucial in our day to day practice, the last decade’s emergence of viable technology and ways which students’ access content and media has reflected this and if anything, lockdown played into their hands.

Faith needs to be restored to music education in a post-COVID climate, and people must trust that cuts to music education will not affect this. Philpott’s (2012) comments duality on music in the curriculum would be a pertinent in today’s climate, worth re-establishing the ‘soft’ (holistic, moral and intellectual) and ‘hard’ (rational, linguistic and liberal) qualities of music and education would benefit if these were looked at to make sure music deserves its place at the table. Given the troubles with coming back to school and the rebuilding of social structure and routine, it might be wise to focus on music’s soft qualities, seeing as contact and interaction are at a premium. By focusing on the social and holistic qualities music can bring first, then build in the rationality this may help students feel better as they re-engage with schools once more without simplifying the challenge that learning music brings, in particular with using DAWs, music educators will need to walk a fine line between the justifications, so as not to condense music technology’s method of creating music into Garage Band’s proverb “If you can tap, you can play” (Bell, 2015, p.62)

If the global success of Playing For Change (which heavily relies on music technology and remote recording to produce performances) is anything to go by, a deeper connection to create music as a community is to happen and make up for the one we lost due to COVID. We can learn that music now must have a broader appeal to society in making it relevant to our lives. The precarious situation with regards to funding to the music industry (https://www.ism.org/news/ism-announces-partnership-musicians-movement) and initial music teacher training (Clifford, 2020) means music’s post-COVID education landscape could send out the wrong signals for both aspiring teachers, the public schools/institutions in their faith with learning and developing music.

References

Ally, M., 2008. Theory and Practice of Online Learning, 2nd ed,. Athabasca, Canada, Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/books/120146/ebook/01_Anderson_2008-Theory_and_Practice_of_Online_Learning.pdf. 5-44

Bell, Adam Patrick. 2015. “Can We Afford These Affordances? GarageBand and the Double-Edged Sword of the Digital Audio Workstation.” Action, Criticism, & Theory for Music Education 14 (1): 44–65.https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rih&AN=A989190&authtype=shib&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Clifford, Harriet, 2020. Music initial teacher training funding withdrawn by Department for Education,www.rhinegold.co.uk. https://www.rhinegold.co.uk/music_teacher/music-initial-teacher-training-funding-withdrawn-by-department-for-education/ (accessed 29/10/2020)

Bauer, William I. 2014. Music Learning Today. [Electronic Resource] : Digital Pedagogy for Creating, Performing, and Responding to Music. Oxford University Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat07554a&AN=jlc.136425&authtype=shib&site=eds-live&scope=site. 60-63

Biasutti, Michele “Assessing a Collaborative Online Environment for Music Composition.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 18, no. 3 (2015): 49-63. Accessed June 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.18.3.49.

Dobson, Elizabeth. 2019. “Talk for Collaborative Learning in Computer-Based Music Production.” Journal of Music, Technology & Education 12 (2): 141–64. doi:10.1386/jmte_00003_1

Dunbar, Laura. 2019. “Creating and Sharing Sound in the Music Classroom.” General MusicToday, 51 (1): 50–51. doi:10.1177/1048371319863799.

Gordon, Edwin. Learning Sequences in Music : A Contemporary Music Learning Theory (2012 Edition). Vol. 2012 edition, GIA Publications, 2012.

Johnson, Carol, and Virginia Christy Lamothe. 2018. Pedagogy Development for Teaching Online Music. Hershey PA: Information Science Reference. 229-231 https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1782037&authtype=shib&site=eds-live&scope=site.

https://reverb.com/news/ways-to-collaborate-on-music-remotely.2020, accessed 29/10/2020

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C., 2003, Knowledge building, 2nd ed.; pp, New York, Macmillan Reference, p. 1370–1373

Swanwick, Keith. Teaching Music Musically. [Electronic Resource]. Routledge, 1999. p13-15-p71-83 https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat07554a&AN=jlc.116615&authtype=shib&site=eds-live&scope=site.