…Seven weeks into lockdown and my eyes are turning into squares, just like Mum used to warn me if I sat too close to the TV watching Beavis and Butthead. The endless playlist of Plan-Teach-Mark is supplemented by my new classroom of sofa, table and an ohh so tempting PS4 complete with Final Fantasy VII Remake. (which has the most beautiful and atmospheric orchestration in video game history, perhaps there’s a blog in video game compositions in the classroom?) I digress, and all joking aside things are going quite well from my remote teaching, better than I expected.

I am fortunate to work in a very supportive school and one open to what is current in today’s teaching, refreshingly so. With the ‘ubiquitousness of technology’ (1) I envision some music departments would have been more prepared than others. By that, I mean more accepting and willing to adapt not only lesson planning, interaction with students but also adapting pedagogy to fit with remote teaching, rather than shoehorning to fit (which I had done in the initial stages).

Much of the buy-in from students comes from how we have created the culture to learn and promote inquisitiveness, my students have been using some form of technology to create music with me over the last three years. During that time, my focus has been on how technology can aid with supporting students and the department itself. (2)

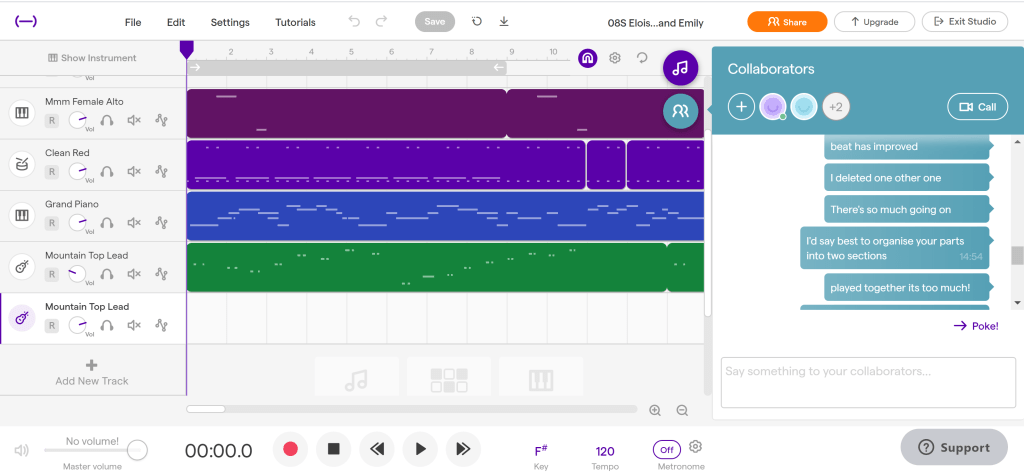

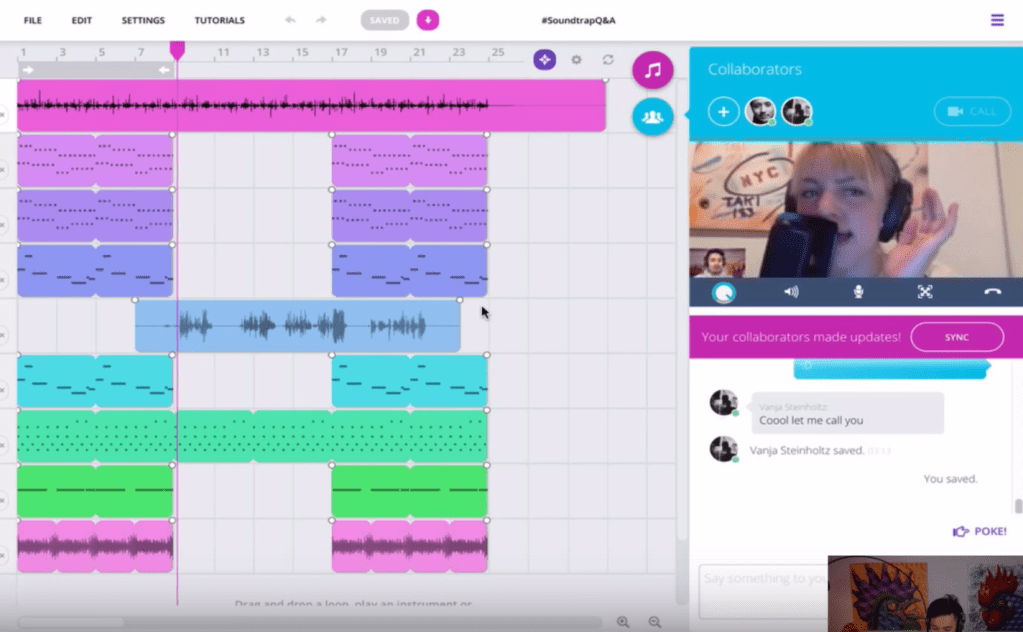

Apps like Soundtrap has made the transition seamless and relatively easy, as covered in my original Remote Learning Blog. The program since then has blown me away in how it manages to engage students into making music with its simple layout and user friendly approach. I think having the right program at hand is crucial to the success of online learning, making sure students have a ‘truly enjoyable cooperative and collaborative conversation that results in deep learning’ (Johnson, Christy Lamothe, 63)

But the best part about it? Realtime collaboration and feedback.

I get constant e-mail updates, even from students who otherwise wouldn’t give music the time of day! And because it’s easy to send messages to me, students feel comfortable and quite assured that I can monitor their work and make suggestions (as seen above). This plays wonderfully into students familiarity with social media.

Remote learning via Soundtrap or use of Microsoft Teams has a crucial role in giving students control of their learning environment, even more than if they would be in my classroom. The lack of dedicated space means some form of an order must be developed and ultimately, self-regulated/policed, even have students delegate roles as teachers too.(4) I have seen many examples of students helping out one another with using various programs, how to upload documents and I often think would that have been the case if they were in class? Would students actively go out of their way to help others struggling in class and take it seriously? Perhaps the severity of the situation coupled with no need to posture or conform in a social group helps this. (5)

Another added bonus of remote teaching is how the online community really stepped up the help. Facebook/Reddit teacher groups or the Music Teachers Association, which I’m member of does wonders for support/morale, and there’s plenty of support for ideas, resources. But what I found surprising is how poorly social media was used pre lockdown for a supportive role in online education, I would think moving forward this will undoubtedly change. I have already seen and felt the tremendous benefits of having a positive and supportive online community for teaching practice. (6)

The pace of the lessons is one that I need to get used to, not only for the wait time when using multiple programs, students logging in or wifi issues. Lesson pacing feels slower and more measured, making sure students understand tasks and feel comfortable completing them, even if they don’t acknowledge via the silent treatment! But there is a benefit to the deliberate pace of online learning, Kathleen Hull acknowledges, “Getting young people to think on their own and solve problems is inefficient, time consuming, and sometimes uncomfortable” (Bender, T. 2012). Students now have time to reflect on my feedback and make changes long after the lesson has finished, perhaps they feel relaxed to do so knowing they don’t have to show progress within the fifty-minute lesson in school. Certainly, the collaborative process helps, reading the comment section of each project shows students working together in a meaningful way, they can add parts to their compositions and have friends make amendments without intruding or offending others (7)

As noted by Picciano, Seaman, and Allen (2010), “adding technology without changing the pedagogy does not necessarily result in any major change to teaching and learning”. I experienced this at the beginning of my remote teaching, naively expecting students to follow the same habits and methods shown in the classroom, albeit in front of a computer. From chatting with various colleagues, it seems we’ve all benefited from tailoring our pedagogy to become more effective markers, assessors, mentors and organisers. Learning how to set up meetings in Teams, sharing screens/PowerPoints and such has forced me to evaluate the content I choose to cover when teaching composition and critique of work, which now has to be more explicit but accessible. By not using my body language and movement, the reliance of aural and visual modelling is forcing me into new ways of communicating with students that I fully intend on keeping once we’re back in the classroom.

One particular area of interest to me is the new online community we find ourselves working and socialising in. I never considered how the lockdown could enforce a sort of ‘Social Constructivist’ framework. Garrison writes about how ‘E-learning’ (remote learning) provides students autonomy in the lesson (Garrison, 2011, p2) and I am trying to build this across my cohorts by making the study materials easier to follow. Soundtrap facilitates a constructivist approach in a way (if collaborating) by allowing a platform for students to design their own lesson and work out their own codes and conduct.

This is not without its flaws, students have to be “active rather than passive” and interoperate the lesson in their own way to learn (Ally, 2008, p. 18). Some students have found this new autonomy in music lessons hard, especially if they’re used to live teacher-directed supervision. The thought of reaching out for help may be hard for them and add in a barrier like remote learning makes it even harder.

Rather than thinking of how students will learn I should have built the structure and culture to learn remotely, teaching students how to use resources to guide them technically and allow more thinking time for them to construct how they see the lesson. I have control in how they first take on information, all I can do is guide, be a presence and observe what they create after they have understood what is asked of them. (8)

I think we’ve all wrestled with the type of content taught in lessons and validness of music tuition under these circumstances. The isolation from the school community and teacher not only disadvantages personal and social growth but it also, at times, makes some lessons feel forced. The very nature of music in schools has been unfairly put aside for ‘core’ subjects, this is keenly felt during remote lessons as those who didn’t buy into music certainly ain’t buying now we have lessons at home! I’d like to think the likes of Soundtrap can help in this regard by making the making of music fun, relevant and authentic to what most kids socialise with now, video games.

The Gamification method has roots in students experiences with video games but aside from this linear pathway, using it in a remote setting has worked when setting tasks which rely on students to complete independent from me. The lack of contact does limit the ‘competitive interaction’ for all, but I think those competing online with FIFA or Fortnite would disagree. Let’s not forget about Kahoot and Quizlet, which were handy pre lockdown and remain popular choices for starter/form activities.

Bibliography:

Ally, M. (2008). Foundations of educational theory for online learning. In T. Anderson (Ed.), Theory and

Practice of Online Learning (2nd ed.; pp. 15–44). Athabasca, Canada: Athabasca University. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/books/120146/ebook/01_Anderson_2008-Theory_and_Practice_of_Online_Learning.pdf

Bender, T. (2012). Discussion-based online teaching to enhance student learning: Theory, practice, and

assessment (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.).

New York, NY: Routledge.

Johnson, Carol, Lamothe, Virginia Christy, 2018, Pedagogy Development for Teaching Online Music, 1st ed, IGI Global

Picciano, A. G., Seaman, J., & Allen, I. E. (2010). Educational transformation through online learning: To be or not to be. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 14(4), 17–35. Retrieved from http://sloanconsortium.org/sites/default/files/2_jaln14-4_picciano.pd

References

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p2

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p3

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p3

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p4, 11, 13

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p46

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, Chapter 12, p244

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p47

- Johnson, Christy Lamothe, p186